What is Patella Luxation?

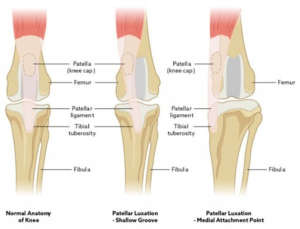

The knee joint connects the femur, (thighbone) and the tibia (shinbone). The patella (kneecap) is normally located in a groove called the trochlear groove, found at the end of the femur. The term luxating means out of place or dislocated. Therefore, a luxating patella is a kneecap that ‘pops out’ or moves out of its normal location.

The degree of luxation is defined with grade ranging from 1 to 4:

Grade 1 – Patella luxates with manual pressure and luxation spontaneously resolves with the release of pressure

Grade 2 – Patellar luxation occurs frequently during stifle flexion or with manual pressure. The patella remains luxated but reduces with manual pressure

Grade 3 – The patella is permanently luxated, but temporary manual reduction is still possible

Grade 4 – The patella is permanently luxated and cannot be manually reduced

What causes Patella luxation?

The cause of patella luxation is multifactorial, and often can’t be pinpointed to one cause. Genetics play a role in patella luxation; some evidence indicates that having 1 parent with patellar luxation increases the incidence in their offspring by 45%. Other anatomical factors include having a shallow trochlear groove, an incongruent patella shape or an abnormally high patella – called Patella Alta. Smaller dogs are more prone to medial patella luxation likely due to the angle of their femur to knee, called the ‘Q-angle’ being a larger degree than in bigger dogs.

What are the symptoms?

The most common sign of a luxating patella is lameness, or a ‘limp’. They may intermittently skip by lifting one hind leg off the ground during a walk or a run. These are often more obvious after a bout of physical activity. In more severe cases, dogs with patellar luxation may hop with both hind legs together when running – called bunny hopping – to try minimising the discomfort caused by the patella.

Other signs and symptoms include a pain response like yelping or whining during activity, stiffness after periods of rest, and swelling around the affected knee joint caused by repeated dislocation.

What breeds is it common in?

Dog breeds most affected tend to be on the small to medium end, and are also almost exclusively a medial patellar luxation (MPL) if they’re a small dog. Interestingly, 75% of Pomeranians have luxation, other breeds more prone include the yorkshire terrier, chihuahua, french bulldog, cavalier king charles spaniel, bichon, pug, bulldog, west highland white terrier, jack russell terrier, shih-tzu, crossbreed and Staffy bull terrier.

Larger dogs can also be affected by patellar luxation, but are more likely to have a lateral luxation because of their anatomy.

Treatment – surgical versus conservative?

A grade 1 luxating patella is mostly managed without surgery. Your animal physiotherapist can assist with releasing tight medial muscles and strengthen lateral muscles through exercise and hydrotherapy to help increase the integrity of your dog’s patellofemoral joint.

A grade 2 luxating patella is more contested in the literature. A study completed in 2020 looked at dogs who had asymptomatic grade 2 luxations and followed them all up after 4 years. 50% of the dogs had to have unscheduled surgery on the affected limb, and 50% continued to be asymptomatic. Both groups did not attend physiotherapy for management of their luxating patella. Further study to demonstrate the benefits of physiotherapy in this group would be ideal, as our experience is very much of benefit in both humans and animals.

Grades 3 and 4 patellar luxations are typically surgically managed, and the recovery period is quite rapid with appropriate pain management. Physiotherapy management can have very positive effects post-operatively in this group, as human studies show that full return to sport and functional activity can be achieved with adequate physiotherapy management after patella reconstruction surgery.